1. Treat reskilling/upskilling as a capability system, not a training program.

2. Start from business outcomes, map the critical work behind them, then define the skills.

3. Focus on the roles and teams sitting at the real bottlenecks; avoid spreading training too thin.

4. Prioritize skills that improve decision speed, execution quality, or risk control.

5. Measure across three layers: adoption in real workflows, performance on critical work, and business impact.

6. Design the “after-skill” path: real projects, coaching, reinforcement in performance reviews, and clear role/mobility outcomes.

Stepping into 2026, one shift has become hard to miss: many companies are choosing to optimize from within, inside the workforce they already have.

Not because ambition has faded. But because operational efficiency is turning into a real constraint. Budgets are tighter. Strategy cycles are shorter. Growth expectations still exist.

In that context, reskilling and upskilling sound like the obvious answer. They’re also some of the easiest strategies to talk about and the hardest to execute. For a simple reason: reskilling and upskilling are not “buying a course.” They are a decision system a way to decide what capability must exist, for whom, by when, and for what purpose.

This piece is a practical view of how to make reskilling and upskilling create business impact, instead of creating the feeling that “we’re doing the right thing.”

Why reskilling and upskilling efforts often fail

A learning program can look flawless on the surface: a polished calendar, strong vendors, high participation, great satisfaction scores. And yet, three to six months later, business results don’t move.

When that happens, the issue is rarely the quality of the course. It tends to come from three blind spots:

- The company isn’t aligned with the target capability, because business priorities are unclear or constantly shifting.

- The company trains the wrong population, spreading efforts too thin to create real momentum at the bottleneck.

- The company lacks a mechanism for the new skill to be used in real work so it never becomes capability.

If you treat reskilling/upskilling as an optimization project, these are the risks you need to lock down early.

Who needs reskilling, and who needs upskilling

Upskilling is when the role stays the same, but the capability bar rises to meet a new performance level.

Reskilling is when the role shifts, or when the company needs to create “new roles” from the workforce it already has.

In practice, I usually start by looking at operational bottlenecks and growth bottlenecks.

Groups that often need upskilling:

- Teams facing higher targets without higher capacity: Sales, CS, Marketing, Ops, Product. Here, upskilling must tie directly to productivity and decision quality.

- Roles with compounding impact: leads/managers, PMs, analysts, system operators. Better capability here changes how whole teams operate.

Groups that often need reskilling:

- Work that is being partially automated or reshaped by systems and AI: manual data entry, reporting, repetitive workflows. Without reskilling, people get stuck doing work that is busy—but not value-creating.

- Areas the company wants to expand without hiring aggressively: data, growth, revops, enablement, QA, security, compliance. The demand is real, but external hiring is slow and risky for fit.

Not everyone needs reskilling/upskilling at the same time. If the company is optimizing, you need to concentrate effort where it creates the biggest performance delta.

Which skills to target so they align with the business

I like one practical rule: a target skill should answer, “Does this help the business decide faster, execute better, or reduce risk more reliably?”

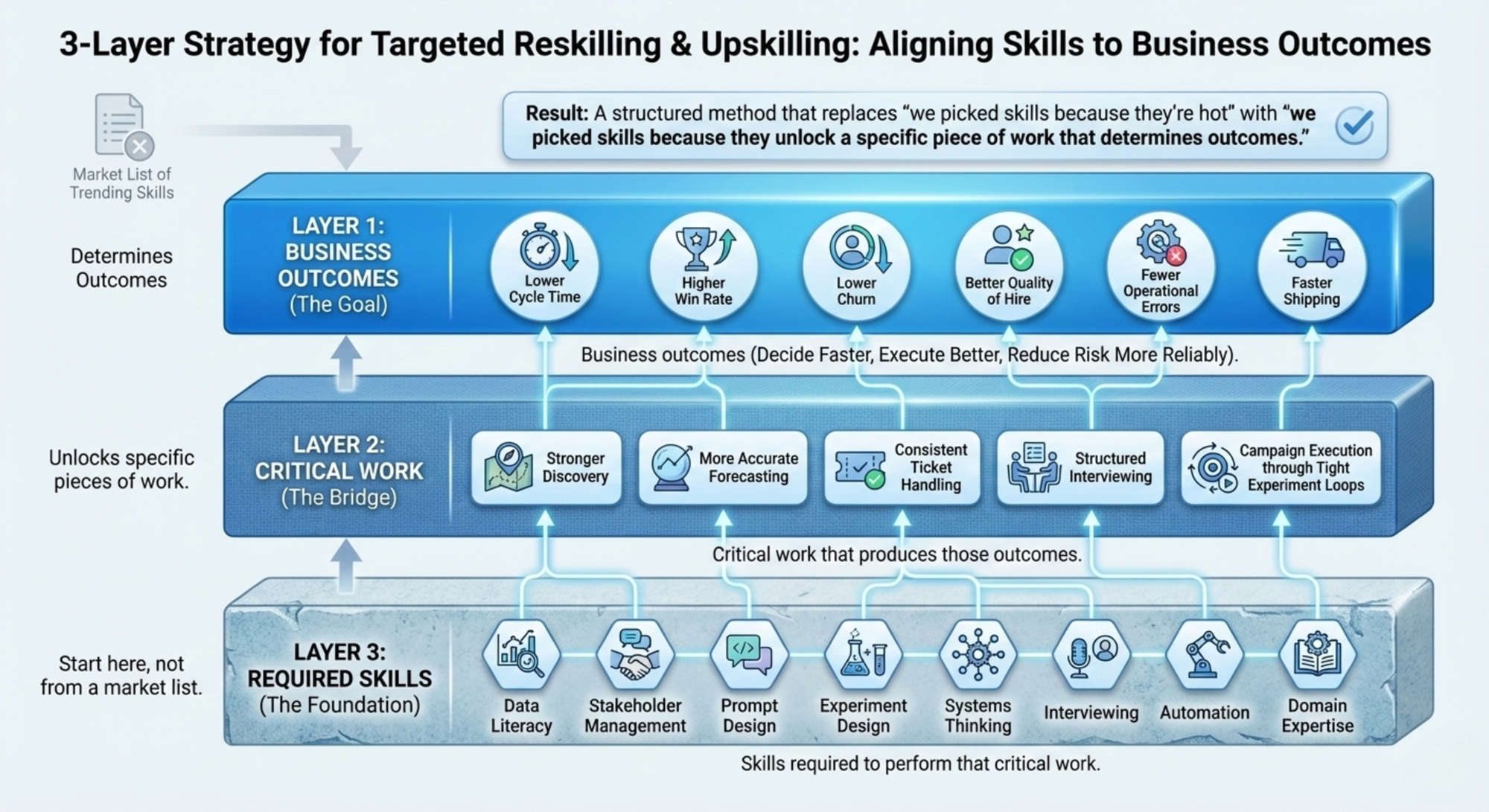

To get there, don’t start from a market list of trending skills. Start from three layers:

Layer 1: Business outcomes

Examples: lower cycle time, higher win rate, lower churn, better quality of hire, fewer operational errors, faster shipping.

Layer 2: Critical work that produces those outcomes

Examples: stronger discovery, more accurate forecasting, consistent ticket handling, structured interviewing, and campaign execution through tight experiment loops.

Layer 3: Skills required to perform that critical work

This is where you name the skills: data literacy, stakeholder management, prompt design, experiment design, systems thinking, interviewing, automation, domain expertise.

This three-layer method prevents “we picked skills because they’re hot,” and replaces it with “we picked skills because they unlock a specific piece of work that determines outcomes.”

How to measure without fooling ourselves

Measuring reskilling and upskilling is hard because it sits between learning and performance. If you only measure completion, you get progress signals without impact. If you only measure final KPIs, you can’t tell whether the program contributed.

I typically measure in three tiers, each answering a different question:

Tier 1: Adoption

Is the new skill used in real work? Did behavior change?

Examples: usage rate of the new process, playbook adoption, standardization of outputs.

Tier 2: Performance on critical work

Did the critical work improve?

Examples: less rework, fewer errors, faster decision cycles, higher accuracy, better handoffs between teams.

Tier 3: Business impact

Did the final outcome move, and where?

Examples: cycle time down, win rate up, churn down, CSAT up, cost-to-serve down.

The advantage of this model is the clarity with which you can see where you’re stuck. If adoption is low, it’s a deployment problem. If adoption is high but performance doesn’t change, it’s a target-skill problem (or a workflow-translation problem). If performance improves but business impact hasn’t appeared, it may be a lag issue, or you may have optimized a part of the system that isn’t large enough to create a visible delta.

What happens after reskilling/upskilling is what decides the outcome

Skills don’t create value by themselves. They create potential. Value only appears when that potential is placed into a clear operating path.

I treat “after-skill” as an operational commitment:

- Is there a real project where the skill must be applied?

- Is there a coach or mentor who can correct the work in context?

- Is there a mechanism to recognize and reinforce the skill in performance evaluation?

- Is there a role path or internal mobility story so people can see a future?

Without this, reskilling and upskilling become symbolic. Well-intentioned, but impact-light.

When companies talk about optimizing the workforce, what they often want is this: create new capability without making the organization heavier.

Reskilling and upskilling can do that but only when they’re designed as a system tied to business priorities, tied to critical work, measured in a way that reveals truth, and supported by a “path” after learning.

If you’re about to run a reskilling/upskilling effort next year, start with this question: which capability, in which group, will create the clearest performance delta for the business in the next six months?

Once you can answer that, the rest becomes far less ambiguous.

Explore TalentsForce Talent Intelligence solution for effective reskilling/upskilling →